Basic Concepts

Heap: In memory management, the heap refers to the area where dynamic memory allocation takes place. This heap is different from the heap in data structures. Once memory is allocated from the heap, it must be manually freed, or it will result in a memory leak.

This concept free store in the C++ standard refers to the area of memory allocated and deallocated using new and delete. Generally speaking, the free store is a subset of the heap:

- The area allocated by

newand deallocated bydeleteis the free store. - The area allocated by

mallocand deallocated byfreeis the heap.

However, new and delete are typically implemented using malloc and free at a lower level, so the free store is also considered part of the heap.

Stack: In memory management, the stack refers to the area where local variables and calling data are stored during function calls. This stack is similar to the stack in data structures, following a last-in-first-out (LIFO) principle.

RAII: Short for Resource Acquisition Is Initialization, RAII is a C++-specific resource management paradigm. RAII uses stack-based objects and destructors to manage all resources, including heap memory. By relying on RAII, C++ does not need garbage collection mechanisms like Java to manage memory effectively. RAII is the primary reason that garbage collection, despite being theoretically possible in C++, has never become popular.

Heap

From a modern programming perspective, using the heap, or dynamic memory allocation, is quite natural. The following code snippets all result in memory being allocated on the heap (and objects being constructed):

// C++

auto ptr = new std::vector<int>();

// Java

ArrayList<int> list = new ArrayList<int>();

# Python

lst = list()

Historically, dynamic memory allocation appeared later due to the uncertainties it introduced—how long does memory allocation take? What happens if it fails? As a result, dynamic memory is still often disabled in many contexts, especially in real-time systems, such as flight controllers and telecom equipment.

Allocating memory on the heap in different languages might use different keywords or might even be done implicitly when constructing objects. Regardless of the method, programs typically involve three types of memory management operations:

- Allocating a block of memory of a specified size.

- Releasing a previously allocated memory block.

- Performing garbage collection to find and free unused memory blocks.

In C++, operations 1 and 2 are usually performed. In Java, operations 1 and 3 are handled. Python typically performs all three operations.

It is worth noting that these operations are not simple and are interrelated.

First, the memory manager needs to consider how much unallocated memory is available. If there’s insufficient memory, it must request more from the operating system. If enough memory is available, it allocates an appropriate block, marks it as used, and returns it to the requesting code.

It’s important to note that in most cases, the available memory will be larger than the requested block, so the remaining unallocated memory stays available for future allocations. Additionally, if the memory manager supports garbage collection, memory allocation may trigger a garbage collection process.

Second, releasing memory is not as simple as marking it as unused. For contiguous blocks of unused memory, the memory manager often needs to merge them into larger blocks to satisfy future memory allocation requests. After all, modern programming requires that allocated memory blocks be contiguous.

Third, garbage collection involves various strategies and implementations designed to balance performance, real-time constraints, and additional overhead.

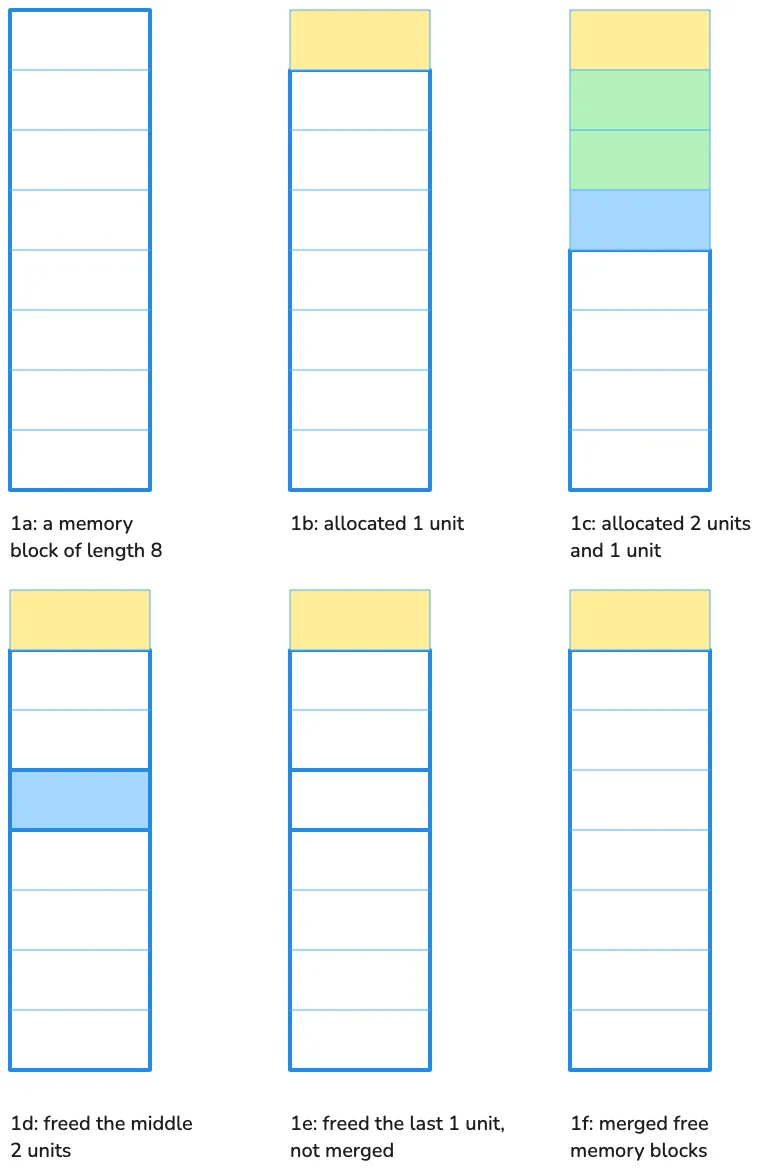

The following figure shows a simple allocation process:

In the state shown in Figure 1e, the memory manager cannot satisfy memory allocation requests larger than 4 in length. However, in the state shown in Figure 1f, any single memory request of length 7 or less can be satisfied.

Of course, this is just a simple illustration to give you an intuitive understanding of the process. Without considering garbage collection, memory needs to be manually freed. During this process, memory fragmentation may occur. For example, in the state shown in Figure 1d, although the total remaining memory is 6, it still cannot satisfy memory allocation requests larger than 4.

Fortunately, most software developers don’t have to worry about this issue. Memory allocation and deallocation management is the responsibility of the memory manager, and in most cases, we don’t need to intervene. We just need to correctly use new and delete. Every object created with new should be freed with delete—it’s that simple.

But is it really that simple and worry-free?

In reality, forgetting to call delete is a common issue known as a “memory leak”—a term you’ve likely heard before. Why does this happen? Let’s look at some code examples.

void foo(){

bar* ptr = new bar();

…

delete ptr;

}

This seems simple, but there are two problems:

- The omitted code in between might throw an exception, preventing

deleteptr from executing. - More importantly, this code does not follow C++ best practices. In C++, 99% of the time, heap allocation should not be used in such cases; instead, stack allocation should be preferred.

A more common and reasonable case is when allocation and deallocation happen in different functions. Consider the following example:

bar* make_bar(…){

bar* ptr = nullptr;

try {

ptr = new bar();

…

}

catch (...) {

delete ptr;

throw;

}

return ptr;

}

void foo(){

…

bar* ptr = make_bar(…);

…

delete ptr;

}

Stack

Let’s examine a simple example to illustrate how function calls and local variables use the stack in C++. Of course, this process depends on the computer’s architecture, and the specific details may vary, but the fundamental principle remains the same: the stack operates as a Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) structure.

void foo(int n){

…

}

void bar(int n){

int a = n + 1;

foo(a);

}

int main(){

…

bar(42);

…

}

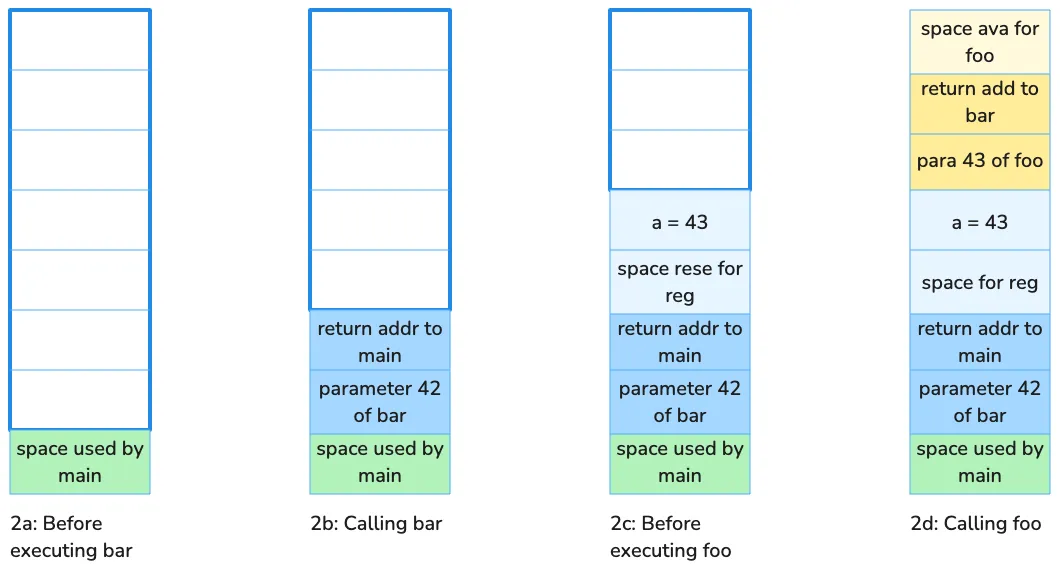

Stack changes during execution of this code:

In our example, the stack grows upwards. In most computer architectures, including x86, the stack grows towards lower addresses, so the upper part represents lower addresses. According to architectural conventions, a function can only use the stack space above the stack pointer when it enters the function. When a function calls another function, it pushes the parameters onto the stack (ignoring cases where registers are used for parameter passing), then pushes the address of the next assembly instruction onto the stack, and jumps to the new function.

Upon entering the new function, it first performs necessary saving operations, then adjusts the stack pointer to allocate space for local variables, executes the function’s code, and after execution, returns to the caller’s unexecuted code using the address pushed onto the stack.

Notice that the memory needed for local variables is on the stack, along with other data required for function execution. Once the function completes, this memory is naturally released. We can observe that:

- Stack allocation is extremely simple, just a stack pointer movement.

- Stack deallocation is also simple, as the stack pointer moves back at function exit.

- Due to the last-in, first-out (LIFO) execution, memory fragmentation does not occur.

By the way, in Figure 2, each color represents the stack space occupied by a particular function. This part of the space has a specific term: stack frame.

In the previous example, the local variables were simple types, referred to as POD (Plain Old Data) in C++. For non-POD types with constructors and destructors, stack memory allocation is still valid, but the C++ compiler automatically inserts calls to constructors and destructors at appropriate positions in the generated code.

A key point here: the compiler automatically calls the destructor, even when a function exits due to an exception. This destructor call during exception handling is called stack unwinding.

Here’s a short piece of code demonstrating stack unwinding:

#include <stdio.h>

class Obj {

public:

Obj() { puts("Obj()"); }

~Obj() { puts("~Obj()"); }

};

void foo(int n){

Obj obj;

if (n == 42)

throw "life, the universe and everything";

}

int main(){

try {

foo(41);

foo(42);

}

catch (const char* s) {

puts(s);

}

}

Running this code produces the following output:

Obj()

~Obj()

Obj()

~Obj()

life, the universe and everything

This shows that whether or not an exception occurs, the destructor for obj is always executed.

In C++, all variables have value semantics by default—if you don’t use * or &, variables don’t reference heap objects like in Java or Python. For types like smart pointers, both ptr->call() and ptr.get() are valid syntax, with -> and . having different meanings. In contrast, many other languages use . for member access, which in effect behaves like -> in C++. This difference between value semantics and reference semantics is a defining characteristic of C++ and a source of its complexity.

RAII

C++ allows objects to be stored on the stack. However, in many situations, objects cannot or should not be stored on the stack, such as when:

- The object is large.

- The object’s size is not known at compile time.

- The object is a function’s return value, but should not be returned by value for special reasons.

A common case is in factory methods or other object-oriented programming scenarios where the return type is a pointer or reference to a base class. Here’s a simple example demonstrating a factory method:

enum class shape_type {

circle,

triangle,

rectangle,

…

};

class shape { … };

class circle : public shape { … };

class triangle : public shape { … };

class rectangle : public shape { … };

shape* create_shape(shape_type type){

…

switch (type) {

case shape_type::circle:

return new circle(…);

case shape_type::triangle:

return new triangle(…);

case shape_type::rectangle:

return new rectangle(…);

…

}

}

The create_shape function returns a shape, but the actual object type is one of shape’s subclasses, such as circle, triangle, or rectangle. In this case, the function must return a pointer or a pointer-like structure. If it returned shape by value, but actually returned a circle, the compiler would not report an error, but the result would likely be incorrect. This issue is known as object slicing, a common C++ programming pitfall.

How do we ensure that the memory allocated by create_shape is not leaked?

The answer lies in destructors and their behavior during stack unwinding. We just need to store the returned pointer in a local variable that ensures proper deletion when the function exits. Here’s a simple implementation:

class shape_wrapper {

public:

explicit shape_wrapper(shape* ptr = nullptr): ptr_(ptr) {}

~shape_wrapper(){

delete ptr_;

}

shape* get() const { return ptr_; }

private:

shape* ptr_;

};

void foo(){

…

shape_wrapper ptr_wrapper(create_shape(…));

…

}

Curious about what happens if you delete a null pointer? The answer is: nothing happens—it’s a valid no-op.

When using new and delete, the compiler does a lot of work behind the scenes. Conceptually, they can be translated into the following steps:

// new circle(…)

{

void* temp = operator new(sizeof(circle));

try {

circle* ptr = static_cast<circle*>(temp);

ptr->circle(…); // Calls the constructor

return ptr;

}

catch (...) {

operator delete(ptr);

throw;

}

}

// delete ptr

if (ptr != nullptr) {

ptr->~shape(); // Calls the destructor

operator delete(ptr);

}

This means, when using new, memory is first allocated. If allocation fails, the operation throws an exception (usually bad_alloc).Then, the object is constructed at the allocated memory location. If the constructor succeeds, the new operation completes. If the constructor throws an exception, the memory is immediately freed before propagating the exception. When calling delete the destructor is called first, but only if the pointer is not nullptr. Then, the previously allocated memory is freed.

Returning to shape_wrapper and its destructor behavior: performing necessary cleanup in the destructor is the fundamental usage of RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization). This cleanup isn’t limited to freeing memory—it can also include:

- Closing files (e.g., fstream does this in its destructor)

- Releasing synchronization locks

- Freeing other important system resources

For example, we should use:

std::mutex mtx;

void some_func(){

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> guard(mtx);

// Perform synchronized work

}

Instead of:

std::mutex mtx;

void some_func(){

mtx.lock();

// Perform synchronized work...

// If an exception occurs or the function returns early,

// the following line won’t be executed automatically.

mtx.unlock();

}

Summary

In this discussion, we covered some fundamental concepts of memory management in C++. We emphasized that the stack is the most “natural” way to use memory in C++. Additionally, using RAII—leveraging stack-based objects and destructors—allows for consistent and effective management of system resources, including heap memory.