In the previous lecture, we introduced a class shape_wrapper that could, to some extent, function as a smart pointer. By using this “smart pointer,” resource management can be simplified, fundamentally eliminating the possibility of resource (including memory) leaks. In this lecture, we’ll take it a step further and demonstrate how to evolve shape_wrapper into a fully functional smart pointer. You’ll see that a smart pointer is essentially a natural extension of RAII for resource management.

Recap

Here’s the class we introduced in the previous lecture:

class shape_wrapper {

public:

explicit shape_wrapper(shape* ptr = nullptr): ptr_(ptr) {}

~shape_wrapper(){

delete ptr_;

}

shape* get() const { return ptr_; }

private:

shape* ptr_;

};

This class achieves the most basic function of a smart pointer: releasing objects that go out of scope. However, it’s missing a few things:

- The class only works for the

shapetype. - The class does not behave like a true pointer.

- Copying objects of this class can lead to unexpected program behavior.

Next, let’s examine how to address these issues one by one.

Templates and Usability

To make our class capable of wrapping pointers of any type, we need to turn it into a class template. This is fairly straightforward:

template <typename T>

class smart_ptr {

public:

explicit smart_ptr(T* ptr = nullptr): ptr_(ptr) {}

~smart_ptr() {

delete ptr_;

}

T* get() const { return ptr_; }

private:

T* ptr_;

};

Compared to shape_wrapper, we simply added a template declaration template <typename T> at the beginning and replaced the shape type with the template parameter T. These changes are simple and intuitive, demonstrating that templates are not inherently complex. Using this template is also easy—just replace shape_wrapper with smart_ptr<shape>.

However, the current smart_ptr still behaves differently from regular pointers:

- It cannot be dereferenced using the

*operator. - It cannot use the

->operator to access members of the pointed-to object. - It cannot be used in boolean expressions like a regular pointer.

These issues can be resolved easily by adding a few member functions:

template <typename T>

class smart_ptr {

public:

...

T& operator*() const { return *ptr_; }

T* operator->() const { return ptr_; }

operator bool() const { return ptr_; }

};

Copy Constructor and Assignment

Handling copy construction and assignment (collectively referred to as “copying”) is a bit more complicated. The challenge lies not in implementation but in defining the desired behavior. Consider the following code:

smart_ptr<shape> ptr1{create_shape(shape_type::circle)};

smart_ptr<shape> ptr2{ptr1};

For the second line, should we cause a compilation error, or allow some reasonable behavior? Let’s examine the possibilities.

The simplest approach is to prohibit copying:

template <typename T>

class smart_ptr {

...

smart_ptr(const smart_ptr&) = delete;

smart_ptr& operator=(const smart_ptr&) = delete;

...

};

Disabling these functions is straightforward and prevents a class of potential errors. Otherwise, smart_ptr<shape> ptr2{ptr1}; would compile but result in undefined behavior at runtime, typically causing a crash due to double deletion of the same memory.

Could we consider copying the pointed-to object instead? No, this is generally not desirable because smart pointers are meant to reduce object copying. Moreover, while our pointer type is shape, it likely points to objects of derived types like circle or triangle. C++ does not have a universal equivalent to Java’s clone method, and there’s no general way to create a subclass object from a base class pointer.

Could we transfer ownership during copying? This can be implemented as follows:

template <typename T>

class smart_ptr {

...

smart_ptr(smart_ptr& other) {

ptr_ = other.release();

}

smart_ptr& operator=(smart_ptr& rhs) {

smart_ptr(rhs).swap(*this);

return *this;

}

...

T* release() {

T* ptr = ptr_;

ptr_ = nullptr;

return ptr;

}

void swap(smart_ptr& rhs) {

using std::swap;

swap(ptr_, rhs.ptr_);

}

...

};

In the copy constructor, ownership is transferred by calling release on the other object. In the assignment operator, a temporary object is created using the copy constructor, and ownership is swapped using swap.

You might have encountered assignment operator implementations with a conditional check like if (this != &rhs). That approach is verbose and lacks strong exception safety—if an exception occurs during assignment, the state of the current object (this) may be partially corrupted.

The idiom shown above ensures strong exception safety. Assignment is divided into two steps: copy construction and swap. An exception can only occur in the first step. If an exception happens during the copy construction, the current object (this) remains unaffected. Thus, the object’s state is either successfully updated or unchanged.

If you find this implementation acceptable, congratulations—you’ve reached the level of the C++ committee in 1998. The semantics here essentially define the auto_ptr class in C++98. However, if you think this implementation feels awkward, congratulations again—the C++ committee felt the same way. As a result, auto_ptr was officially removed from the C++ standard in C++17.

The main issue with the above implementation is that it makes it easy for programmers to make mistakes. If you inadvertently pass ownership to another smart_ptr, you lose access to the object…

“Move” Semantics for Smart Pointers

In the next section, we’ll provide a complete introduction to move semantics. For now, let’s take a brief look at how smart_ptr can leverage “move” semantics to improve their behavior.

We need to make two small modifications to the code:

template <typename T>

class smart_ptr {

...

smart_ptr(smart_ptr&& other) { // Move constructor

ptr_ = other.release();

}

smart_ptr& operator=(smart_ptr rhs) { // Assignment operator

rhs.swap(*this);

return *this;

}

...

};

What’s Changed?

- The parameter type of the copy constructor was changed from

smart_ptr&tosmart_ptr&&. This makes it a move constructor. - The parameter type of the assignment operator was changed from

smart_ptr&tosmart_ptr. This allows the function to directly generate a new smart pointer during construction, eliminating the need to create a temporary object within the function. The behavior of the assignment operator—whether it involves a move or a copy—depends entirely on whether the constructor invoked is the move constructor or copy constructor.

According to C++ rules, if a move constructor is provided and a copy constructor is not explicitly defined, the latter is automatically disabled. As a result, the following behavior is naturally achieved:

smart_ptr<shape> ptr1{create_shape(shape_type::circle)};

smart_ptr<shape> ptr2{ptr1}; // Compilation error

smart_ptr<shape> ptr3;

ptr3 = ptr1; // Compilation error

ptr3 = std::move(ptr1); // OK, ownership is transferred

smart_ptr<shape> ptr4{std::move(ptr3)}; // OK, ownership is transferred

This behavior is intuitive and aligns with the basic behavior of std::unique_ptr in C++11.

Converting Subclass to Base Class Pointers

You may have noticed that while a circle* can implicitly convert to a shape*, a smart_ptr<circle> cannot automatically convert to a smart_ptr<shape>. This behavior is less “natural.”

To address this, we only need to add a template constructor to the implementation. Here’s the modification:

template <typename U>

smart_ptr(smart_ptr<U>&& other) {

ptr_ = other.release();

}

By adding this, we naturally utilize pointer conversion properties. Now, a smart_ptr<circle> can be moved to a smart_ptr<shape> but not to a smart_ptr<triangle>. Invalid conversions will result in compilation errors.

Note: This template constructor is not considered a move constructor by the compiler, so it doesn’t automatically disable the copy constructor. To avoid redundant code or to explicitly prohibit copy construction, you can mark the copy constructor as = delete (as discussed in the “Copy Constructor and Assignment” section). For a more general solution, both standard copy/move constructors and template constructors should be explicitly defined.

Reference Counting for Shared Ownership

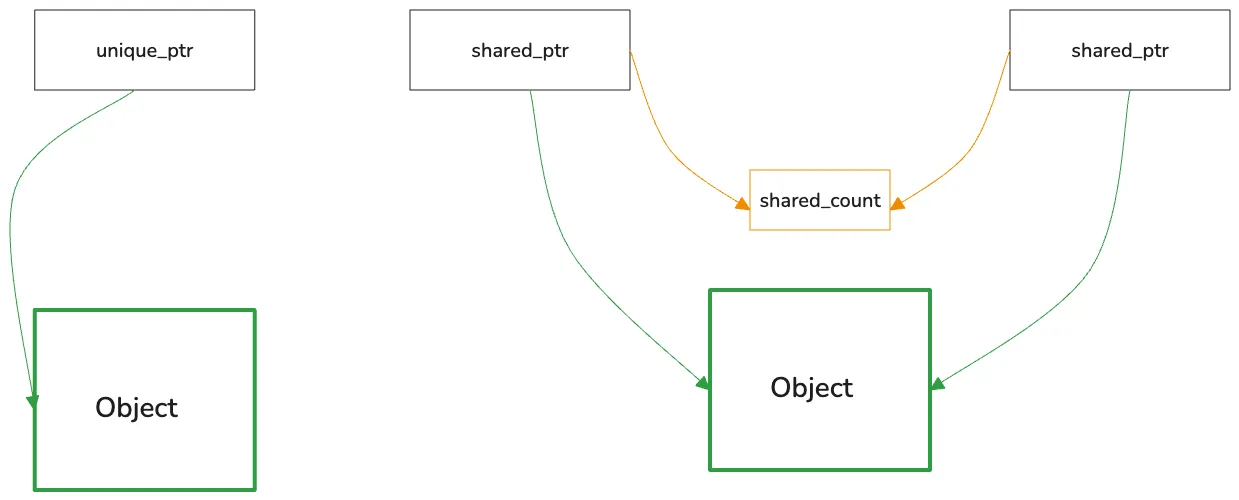

While unique_ptr provides safe smart pointer functionality, it limits ownership to a single pointer, which isn’t suitable for all use cases. A common scenario is when multiple smart pointers share ownership of the same object, and the object is deleted only when all of them are destroyed. This is the basis of shared_ptr.

The main differences between unique_ptr and shared_ptr are illustrated below:

Multiple shared_ptr instances can share ownership of the same object. Shared pointers need to maintain a reference count, which is shared among all instances pointing to the same object. The last shared_ptr to release the object is responsible for deleting it and the reference count.

We begin by implementing a shared_count class:

class shared_count {

public:

shared_count();

void add_count();

long reduce_count();

long get_count() const;

};

The class provides three methods: one to increment the count, one to decrement the count, and one to retrieve the current count. Incrementing doesn’t return a value, but decrementing does so that the caller can determine if this is the last shared_ptr pointing to the object.

For simplicity, we’ll implement a basic version without multithreading considerations:

class shared_count {

public:

shared_count() : count_(1) {}

void add_count() {

++count_;

}

long reduce_count() {

return --count_;

}

long get_count() const {

return count_;

}

private:

long count_;

};

Now we can implement our reference-counted smart pointer. First, let’s define the constructor, destructor, and private members:

template <typename T>

class smart_ptr {

public:

explicit smart_ptr(T* ptr = nullptr): ptr_(ptr) {

if (ptr) {

shared_count_ = new shared_count();

}

}

~smart_ptr() {

if (ptr_ && !shared_count_->reduce_count()) {

delete ptr_;

delete shared_count_;

}

}

private:

T* ptr_;

shared_count* shared_count_;

};

The constructor initializes a shared_count if the pointer is non-null. The destructor decreases the reference count and deletes the object and count when the reference count drops to zero.

To facilitate assignment and other operations, we add a swap function:

void swap(smart_ptr& rhs) {

using std::swap;

swap(ptr_, rhs.ptr_);

swap(shared_count_, rhs.shared_count_);

}

The copy and move constructors need updates:

smart_ptr(const smart_ptr& other) {

ptr_ = other.ptr_;

if (ptr_) {

other.shared_count_->add_count();

shared_count_ = other.shared_count_;

}

}

template <typename U>

smart_ptr(const smart_ptr<U>& other) {

ptr_ = other.ptr_;

if (ptr_) {

other.shared_count_->add_count();

shared_count_ = other.shared_count_;

}

}

template <typename U>

smart_ptr(smart_ptr<U>&& other) {

ptr_ = other.ptr_;

if (ptr_) {

shared_count_ = other.shared_count_;

other.ptr_ = nullptr;

}

}

For the copy constructor, we increment the reference count if the pointer is non-null and copy the shared count. For the move constructor, we transfer ownership by nullifying the original pointer and sharing the shared_count.

The code above has a problem: it won’t compile.

The compiler throws an error because template instances don’t inherently have friend relationships with each other. This means they can’t access private members like ptr_ and shared_count_ across different template instantiations. To resolve this, we need to explicitly declare:

template <typename U>

friend class smart_ptr;

In the previous implementation, which resembled a single-ownership unique_ptr, we used release to manually transfer ownership. However, in the current reference-counting implementation, release is no longer suitable and should be removed.

Instead, we can add a function that is very useful for debugging: it returns the reference count. Here’s the definition:

long use_count() const {

if (ptr_) {

return shared_count_->get_count();

} else {

return 0;

}

}

This gives us a more complete implementation of a reference-counted smart pointer. Let’s test its functionality with the following code:

class shape {

public:

virtual ~shape() {}

};

class circle : public shape {

public:

~circle() { puts("~circle()"); }

};

int main() {

smart_ptr<circle> ptr1(new circle());

printf("use count of ptr1 is %ld\n", ptr1.use_count());

smart_ptr<shape> ptr2;

printf("use count of ptr2 was %ld\n", ptr2.use_count());

ptr2 = ptr1;

printf("use count of ptr2 is now %ld\n", ptr2.use_count());

if (ptr1) {

puts("ptr1 is not empty");

}

}

Expected Output

use count of ptr1 is 1

use count of ptr2 was 0

use count of ptr2 is now 2

ptr1 is not empty

~circle()

From this output, we can observe the changes in the reference count and confirm that the object is successfully deleted when the last smart_ptr instance goes out of scope.

Pointer Type Conversion

In C++, we have different types of explicit type casts:

- static_cast

- reinterpret_cast

- const_cast

- dynamic_cast

Smart pointers should implement similar functionality through function templates. This isn’t particularly complex to implement, but enabling such conversions requires adding a constructor that accepts an existing smart pointer’s reference count when assigning the internal pointer. Here’s how it looks:

template <typename U>

smart_ptr(const smart_ptr<U>& other, T* ptr) {

ptr_ = ptr;

if (ptr_) {

other.shared_count_->add_count();

shared_count_ = other.shared_count_;

}

}

Using this, we can implement a conversion function, such as dynamic_pointer_cast. Here’s an example:

template <typename T, typename U>

smart_ptr<T> dynamic_pointer_cast(const smart_ptr<U>& other) {

T* ptr = dynamic_cast<T*>(other.get());

return smart_ptr<T>(other, ptr);

}

To test this, add the following code after the previous test:

smart_ptr<circle> ptr3 = dynamic_pointer_cast<circle>(ptr2);

printf("use count of ptr3 is %ld\n", ptr3.use_count());

Additional Output

use count of ptr3 is 3

The object will still be correctly deleted when the last smart_ptr instance is destroyed, demonstrating the correctness of our implementation.

Full smart_ptr Code Listing

For reference, here’s the complete implementation of smart_ptr:

#include <utility> // std::swap

class shared_count {

public:

shared_count() noexcept

: count_(1) {}

void add_count() noexcept{

++count_;

}

long reduce_count() noexcept{

return --count_;

}

long get_count() const noexcept{

return count_;

}

private:

long count_;

};

template <typename T>

class smart_ptr {

public:

template <typename U>

friend class smart_ptr;

explicit smart_ptr(T* ptr = nullptr): ptr_(ptr) {

if (ptr) {

shared_count_ = new shared_count();

}

}

~smart_ptr(){

if (ptr_ &&!shared_count_->reduce_count()) {

delete ptr_;

delete shared_count_;

}

}

smart_ptr(const smart_ptr& other){

ptr_ = other.ptr_;

if (ptr_) {

other.shared_count_->add_count();

shared_count_ = other.shared_count_;

}

}

template <typename U>

smart_ptr(const smart_ptr<U>& other) noexcept{

ptr_ = other.ptr_;

if (ptr_) {

other.shared_count_->add_count();

shared_count_ = other.shared_count_;

}

}

template <typename U>

smart_ptr(smart_ptr<U>&& other) noexcept{

ptr_ = other.ptr_;

if (ptr_) {

shared_count_ = other.shared_count_;

other.ptr_ = nullptr;

}

}

template <typename U>

smart_ptr(const smart_ptr<U>& other,T* ptr) noexcept{

ptr_ = ptr;

if (ptr_) {

other.shared_count_->add_count();

shared_count_ = other.shared_count_;

}

}

smart_ptr& operator=(smart_ptr rhs) noexcept{

rhs.swap(*this);

return *this;

}

T* get() const noexcept{

return ptr_;

}

long use_count() const noexcept{

if (ptr_) {

return shared_count_->get_count();

} else {

return 0;

}

}

void swap(smart_ptr& rhs) noexcept{

using std::swap;

swap(ptr_, rhs.ptr_);

swap(shared_count_, rhs.shared_count_);

}

T& operator*() const noexcept{

return *ptr_;

}

T* operator->() const noexcept{

return ptr_;

}

operator bool() const noexcept{

return ptr_;

}

private:

T* ptr_;

shared_count* shared_count_;

};

template <typename T>

void swap(smart_ptr<T>& lhs, smart_ptr<T>& rhs) noexcept{

lhs.swap(rhs);

}

template <typename T, typename U>

smart_ptr<T> static_pointer_cast(const smart_ptr<U>& other) noexcept{

T* ptr = static_cast<T*>(other.get());

return smart_ptr<T>(other, ptr);

}

template <typename T, typename U>

smart_ptr<T> reinterpret_pointer_cast(const smart_ptr<U>& other) noexcept{

T* ptr = reinterpret_cast<T*>(other.get());

return smart_ptr<T>(other, ptr);

}

template <typename T, typename U>

smart_ptr<T> const_pointer_cast(const smart_ptr<U>& other) noexcept{

T* ptr = const_cast<T*>(other.get());

return smart_ptr<T>(other, ptr);

}

template <typename T, typename U>

smart_ptr<T> dynamic_pointer_cast(const smart_ptr<U>& other) noexcept{

T* ptr = dynamic_cast<T*>(other.get());

return smart_ptr<T>(other, ptr);

}

Summary

In this lesson, we started with a basic shape_wrapper implementation and built a reference-counted smart pointer. While our smart_ptr lacks some features compared to std::shared_ptr, it includes most of the commonly used functionalities. By now, you should have a deeper understanding of smart pointers and how they work.