What is an Iterator?

An iterator is a very general concept — it’s not a specific type, but rather a set of requirements for a type. At its core, an iterator allows you to move from one position to another, step by step, until you reach the end. In Chinese, perhaps the term “traverse” would be more accurate than “iterate.” For example, you can traverse:

- The characters of a string,

- The contents of a file,

- All files in a directory, and so on. These can all be expressed using iterators.

When I use output_container.h to output the contents of a container, I’m actually relying on certain requirements for the types returned by the container’s begin and end member functions. Suppose begin returns a type I and end returns a type S. The requirements are:

- Objects of type

Isupport the dereference operator*, to access the element inside the container. - Objects of type

Isupport++, to move to the next element. - Objects of type

Ican be compared for equality with otherIorSobjects, to check whether we’ve reached a particular position (forS, usually meaning the end of traversal).

Note that prior to C++17, begin and end had to return the same type. Starting with C++17, I and S may be different types, which allows for greater flexibility and more optimization opportunities.

The type I described above basically satisfies the requirements for an input iterator. However, output_container.h only uses the prefix ++, while input iterators require both prefix and postfix ++ to be supported.

Input iterators don’t require the ability to dereference *i multiple times or to store the iterator for later reuse. In other words, they allow single-pass access.If these restrictions are relaxed (allowing multiple dereferences and re-visiting elements), the iterator qualifies as a forward iterator.

If a forward iterator also supports -- (both prefix and postfix), allowing movement backward, it becomes a bidirectional iterator, meaning it can traverse both forwards and backwards.

If a bidirectional iterator further supports: Arithmetic operations like +, -, +=, -= with integer values, Array-style access via [], Ordering comparisons (not just equality), then it qualifies as a random-access iterator.

For a random-access iterator i and an integer n, if *i is valid and i + n produces a valid iterator, and additionally *(address_of(*i) + n) is equivalent to *(i + n) — meaning the elements are stored contiguously in memory — then it qualifies (in C++20) as a contiguous iterator.

The iterators discussed above focus on reading. If a type behaves like an input iterator but *i can only be used for writing (as an lvalue), not reading, then it’s called an output iterator.

Both input and output iterators are built on top of a more basic concept — the iterator itself. At the most fundamental level, an iterator must:

- Be copy-constructible, copy-assignable, and destructible.

- Support the dereference operator

*. - Support prefix

++.

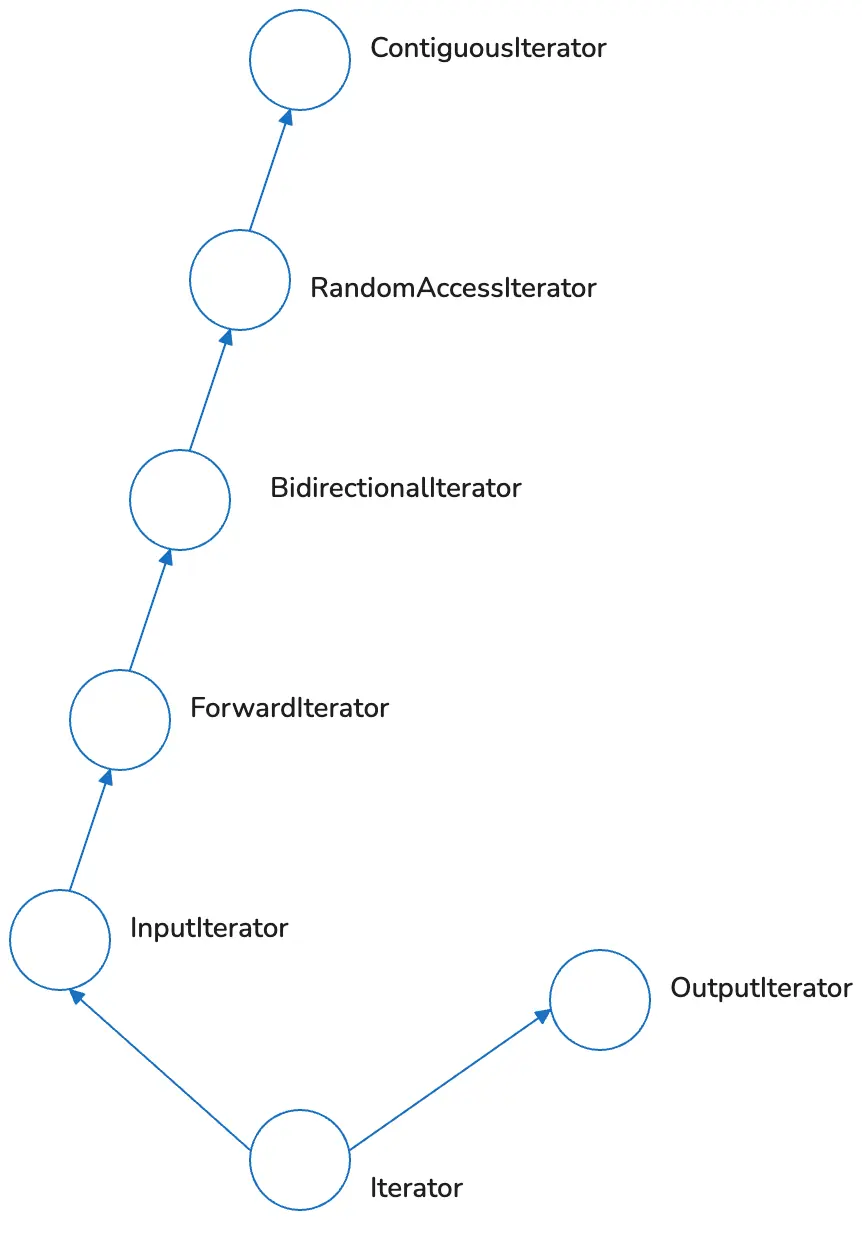

The relationships between the different iterator categories can be visualized as follows:

While iterators are usually objects, it’s important to note that raw pointers also satisfy all of these iterator requirements — they are valid iterators. This shouldn’t be surprising, since the entire iterator concept was essentially abstracted from the behavior of pointers. In fact, in many implementations, a vector’s iterator is simply a raw pointer.

Common Iterators

The most commonly used iterators are the container’s iterator types. Taking the sequence containers we’ve studied as examples, they all define nested iterator and const_iterator types. Generally speaking, iterator allows writing, while const_iterator is read-only. These iterators are defined as input iterators or their derived types:

vector::iteratorandarray::iteratormeet the requirements for contiguous iterators.deque::iteratorsatisfies random access iterator (remember, deque’s memory is only partially contiguous).list::iteratorsatisfies bidirectional iterator (linked lists can’t jump directly to arbitrary positions).forward_list::iteratorsatisfies forward iterator (singly linked lists can’t traverse backward).

A common example of an output iterator is the type returned by back_inserter, called back_inserter_iterator, which makes it convenient to insert elements at the back of a container. Another common output iterator is ostream_iterator, which makes it easy to “copy” container contents into an output stream. For example:

vector<int> v1{1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

vector<int> v2;

copy(v1.begin(), v1.end(), back_inserter(v2));

Using an Input Line Iterator

Next, let’s look at an input iterator I wrote. Its function is simple: read the contents of an input stream (istream) line by line. Thanks to the range-based for loop syntax introduced in C++11, we can write traversal code for input streams in a very natural, non-procedural way, like this:

for (const string& line : istream_line_reader(is)) {

// Example loop body: simply print each line

cout << line << endl;

}

Now compare that with traditional C++ code, which requires more boilerplate:

string line;

for (;;) {

getline(is, line);

if (!is) {

break;

}

cout << line << endl;

}

With the earlier code, reading lines from is is handled in a single statement; here, we need 5 statements.

We’ll analyze this input iterator later. But first, let’s explain how range-based for loops work. Although it’s essentially syntactic sugar, it significantly improves code readability. Without this sugar, much of the conciseness is lost. Here’s how this loop would be expanded into a regular for loop:

{

auto&& r = istream_line_reader(is);

auto it = r.begin();

auto end = r.end();

for (; it != end; ++it) {

const string& line = *it;

cout << line << endl;

}

}

You can see that it’s not very complicated. The compiler essentially does:

- Evaluate the expression after the colon and implicitly store a reference to its result (

r), valid for the entire loop. According to lifetime extension rules, if the result is a temporary object, its destruction is delayed until after the loop. - Automatically generate iterators by calling

beginandendon the range. - Within the loop body, automatically declare and initialize the loop variable (on the left-hand side of the colon) using

*it. - The actual loop body follows.

The generation of iterators may or may not involve calling r’s member functions begin and end. The exact rule is:

- For C arrays (only if they haven’t decayed into pointers), the compiler automatically generates pointers to the beginning and end of the array (essentially applying

std::beginandstd::endfor arrays). - For objects with

beginandendmember functions, the compiler calls those member functions (as in our current case). - Otherwise, the compiler tries to find non-member

begin(r)andend(r)functions in the same namespace asr, and call them. If it cannot find suitable functions, compilation fails with an error.

Defining an Input Line Iterator

Now let’s look at what we need to do to implement this input line iterator.

C++ has some standard type requirements for iterators. For an iterator, we need to define the following types:

class istream_line_reader {

public:

class iterator { // Implements InputIterator

public:

typedef ptrdiff_t difference_type;

typedef string value_type;

typedef const value_type* pointer;

typedef const value_type& reference;

typedef input_iterator_tag iterator_category;

…

};

…

};

Following the typical container pattern, we define the iterator as a nested class inside istream_line_reader. These five type definitions are required (other generic C++ code may rely on them). The standard library used to provide a base class template std::iterator to help generate these type definitions, but that has been deprecated . Here’s what each type means:

difference_type: Represents the distance between two iterators. Defining it asptrdiff_tis a standard practice (pointer difference type), though this type isn’t directly used here.value_type: The type of value the iterator points to. Here, we usestring, meaning the iterator points to strings.pointer: The pointer type for the objects the iterator refers to. We simply define it as a const pointer tovalue_type(we don’t want others modifying the pointed-to content).reference: A const reference tovalue_type.iterator_category: Defined asinput_iterator_tag, indicating that this iterator is an input iterator.

For true input iterators that can only be read once, there’s a particular design decision (which doesn’t apply to forward iterators and their descendants):

Should * or ++ be responsible for performing the read operation? Here, we use the common and simpler approach: let ++ handle reading, while * simply returns the previously read value. (This design has some side effects but works fine for our usage.)

Following this design, the iterator needs:

- A data member pointing to the input stream.

- A data member to store the currently read line.

Here’s the basic definition of the class:

class istream_line_reader {

public:

class iterator {

…

iterator() noexcept : stream_(nullptr) {}

explicit iterator(istream& is) : stream_(&is) {

++*this;

}

reference operator*() const noexcept {

return line_;

}

pointer operator->() const noexcept {

return &line_;

}

iterator& operator++() {

getline(*stream_, line_);

if (!*stream_) {

stream_ = nullptr;

}

return *this;

}

iterator operator++(int) {

iterator temp(*this);

++*this;

return temp;

}

private:

istream* stream_;

string line_;

};

…

};

We define a default constructor that clears stream_. In the constructor with a parameter, we assign the provided stream to stream_, and immediately call ++ to perform the first read so that * can be used right after construction, following the common convention of dereferencing before incrementing.

Once we reach the end of the file (or encounter an error), stream_ is reset to nullptr, which matches the default-constructed iterator state.

For comparing two iterators, we primarily care about whether the stream has reached its end:

bool operator==(const iterator& rhs) const noexcept {

return stream_ == rhs.stream_;

}

bool operator!=(const iterator& rhs) const noexcept {

return !operator==(rhs);

}

With the iterator defined, the istream_line_reader class itself is very simple:

class istream_line_reader {

public:

class iterator { … };

istream_line_reader() noexcept : stream_(nullptr) {}

explicit istream_line_reader(istream& is) noexcept : stream_(&is) {}

iterator begin() { return iterator(*stream_); }

iterator end() const noexcept { return iterator(); }

private:

istream* stream_;

};

In short:

- The constructor just stores a pointer to the provided input stream.

begin()returns a valid iterator that starts reading from the stream.end()returns a default-constructed iterator, which represents the end of iteration.

This completes a fully functional line-based input stream iterator.