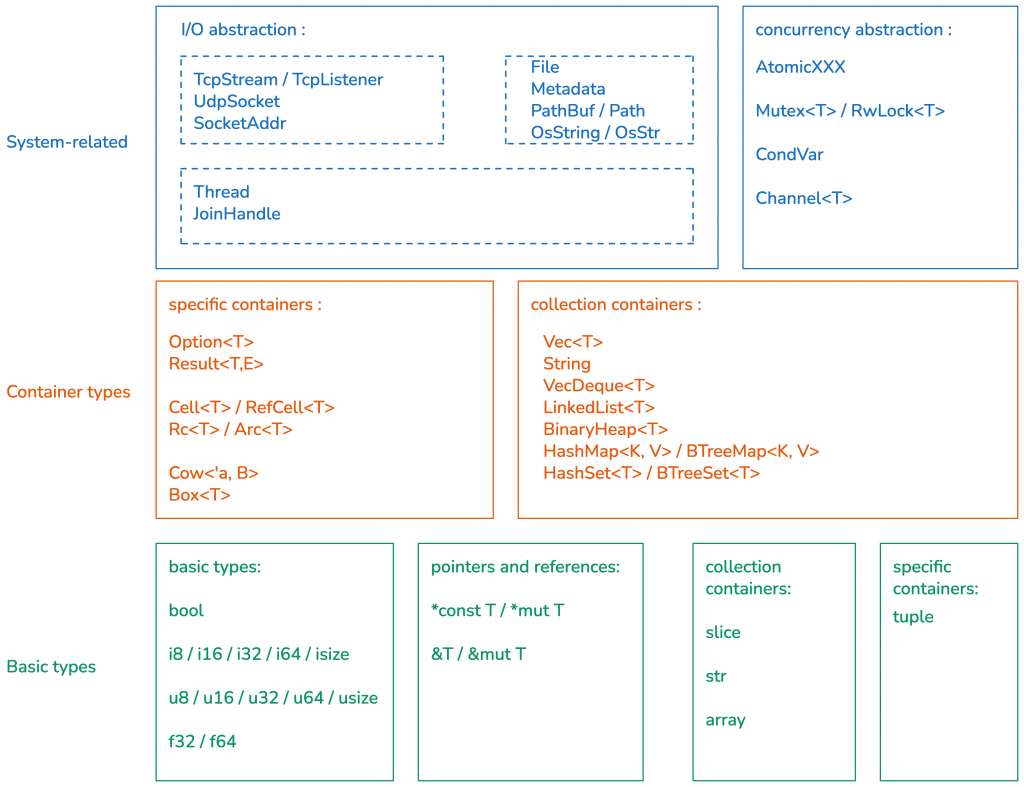

Now that we have encountered more and more data structures, I have organized the main data structures in Rust from the dimensions of primitive types, container types, and system-related types. You can count how many you have mastered.

As you can see, containers occupy half of the data structure landscape.

When mentioning containers, you may first think of arrays and lists—containers that can be iterated. But in fact, as long as some specific data is wrapped inside a data structure, that data structure is itself a container. For example, Option<T> is a container wrapping whether T exists or not, while Cow is a container encapsulating whether the internal data B is borrowed or owned.

Among the two small categories of containers, so far we have already introduced many containers like Cow that are created for specific purposes, including Box, Rc, Arc, RefCell, and the still-to-be-discussed Option and Result.

Today we will discuss in detail another category: collection containers.

Collection Containers

Collection containers, as the name suggests, put together a series of data with the same type and handle them uniformly. For example:

- familiar strings such as

String, arrays[T; n], listsVec<T>, hash mapsHashMap<K, V>; - slice, which we use all the time but are not yet fully familiar with;

- circular buffers like

VecDeque<T>and doubly linked listsLinkedList<T>, which you may have used in other languages but not yet in Rust.

These collection containers have many things in common — they can be iterated, they support map-reduce operations, they can be converted from one type to another, etc.

We will select two typical kinds: slice and hash maps, to analyze in depth. Once you understand these two, the design ideas behind all other collection containers become similar and not difficult to learn.

What Exactly Is a Slice?

In Rust, a slice describes a group of data of the same type, with an unknown length, stored continuously in memory, expressed as [T]. Because the length is unknown, slice are DSTs (Dynamically Sized Types).

Slice mainly appear in type definitions and cannot be accessed directly. In actual use, they appear mainly in the following forms:

&[T]: a read-only slice reference&mut [T]: a writable slice referenceBox<[T]>: a slice allocated on the heap

How should we understand slice? Let me use an analogy: a slice to concrete data structures is like a view to a table in a database. You can think of it as a tool that allows us to uniformly access types that behave similarly and have similar structures but with small differences.

Look at the following code to help you understand:

fn main() {

let arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let vec = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let s1 = &arr[..2];

let s2 = &vec[..2];

println!("s1: {:?}, s2: {:?}", s1, s2);

// Whether &[T] and &[T] are equal depends on whether length and content are equal

assert_eq!(s1, s2);

// &[T] can be compared with Vec<T> / [T; n], also based on length and content

assert_eq!(&arr[..], vec);

assert_eq!(&vec[..], arr);

}

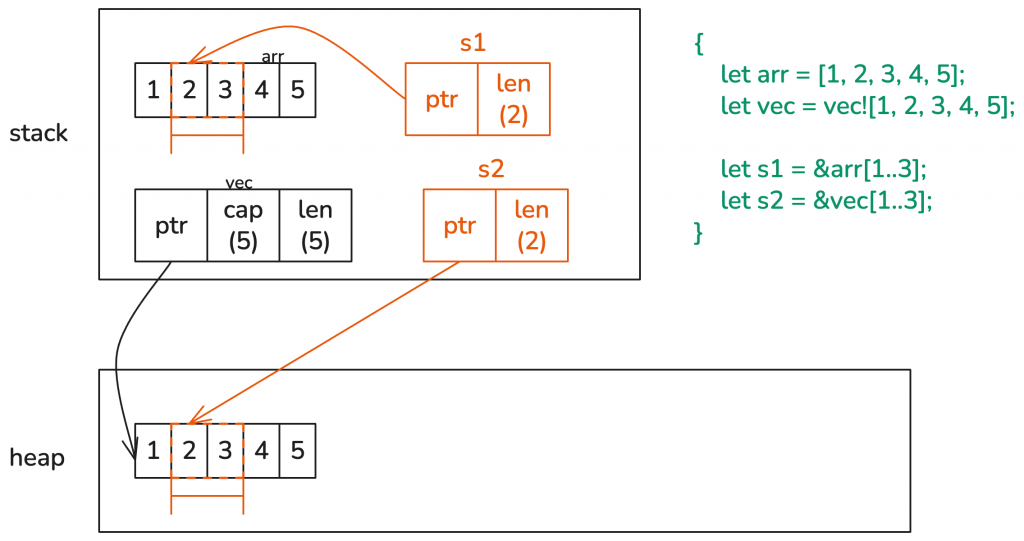

Although an array and a vector are different data structures—one stored on the stack, the other on the heap—their slice are similar. And for slice of the same content, such as &arr[1..3] and &vec[1..3], these two are equivalent. Additionally, slice and their underlying data structures can be compared directly because they implement the PartialEq trait.

The following figure clearly shows the relationship between slice and data:

Additionally, in Rust, we use references to slice (&[T]) in daily life, so many learners easily get confused about the difference between &[T] and &Vec<T>.

I drew a diagram to help you better understand their relationship:

![the difference between &[T] and &Vec<T>](https://binarymusings.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/rust-16-03-1024x570.png)

When using types that support slice, you can convert them into slice types through dereferencing when needed. For example, Vec<T> and [T; n] will be converted into [T], because Vec implements Deref, and arrays have built-in dereferencing to [T].

We can write code to verify this behavior:

use std::fmt;

fn main() {

let v = vec![1, 2, 3, 4];

// Vec implements Deref, so &Vec<T> is automatically dereferenced to &[T], matching the interface definition

print_slice(&v);

// Already &[T], matching the interface definition

print_slice(&v[..]);

// &Vec<T> supports AsRef<[T]>

print_slice1(&v);

// &[T] supports AsRef<[T]>

print_slice1(&v[..]);

// Vec<T> also supports AsRef<[T]>

print_slice1(v);

let arr = [1, 2, 3, 4];

// Although arrays do not implement Deref, their dereference is &[T]

print_slice(&arr);

print_slice(&arr[..]);

print_slice1(&arr);

print_slice1(&arr[..]);

print_slice1(arr);

}

// Note the usage of the generic function below

fn print_slice<T: fmt::Debug>(s: &[T]) {

println!("{:?}", s);

}

fn print_slice1<T, U>(s: T)

where

T: AsRef<[U]>,

U: fmt::Debug,

{

println!("{:?}", s.as_ref());

}

This means that through dereferencing, these slice-related data structures all obtain all slice capabilities, including: binary_search, chunks, concat, contains, start_with, end_with, group_by, iter, join, sort, split, swap and many other powerful functions. You can refer to the slice documentation.

slice and the Iterator

Iterators can be said to be the twin brothers of slice. A slice is a view of collection data, while an iterator defines various access operations over collection data.

Through the iter() method of a slice, we can generate an iterator to iterate over the slice.

In this article Rust Type Inference, we have already seen the iterator trait (using the collect method to form a new list from filtered data). The iterator trait has a large number of methods, but in most cases, we only need to define its associated type Item and the next() method.

Itemdefines the type of data we get from the iterator each time;next()is the method to get the next value from the iterator. When an iterator’snext()returnsNone, it means there is no more data in the iterator.

#[must_use = "iterators are lazy and do nothing unless consumed"]

pub trait Iterator {

type Item;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item>;

// A large number of default methods, including size_hint, count, chain, zip, map,

// filter, for_each, skip, take_while, flat_map, flatten

// collect, partition, etc.

...

}

Look at an example. Using iter() on Vec<T> and performing various map / filter / take operations. In functional programming languages, such expressions are very common and very readable. Rust also supports this style:

fn main() {

// Here Vec<T> is dereferenced into &[T] when calling iter(), so iter() can be accessed

let result = vec![1, 2, 3, 4]

.iter()

.map(|v| v * v)

.filter(|v| *v < 16)

.take(1)

.collect::<Vec<_>>();

println!("{:?}", result);

}

Note that iterators in Rust are a lazy interface, meaning this code does not actually run until it reaches collect. All earlier parts are just continually generating new structures to accumulate processing logic. You may wonder, how is this done?

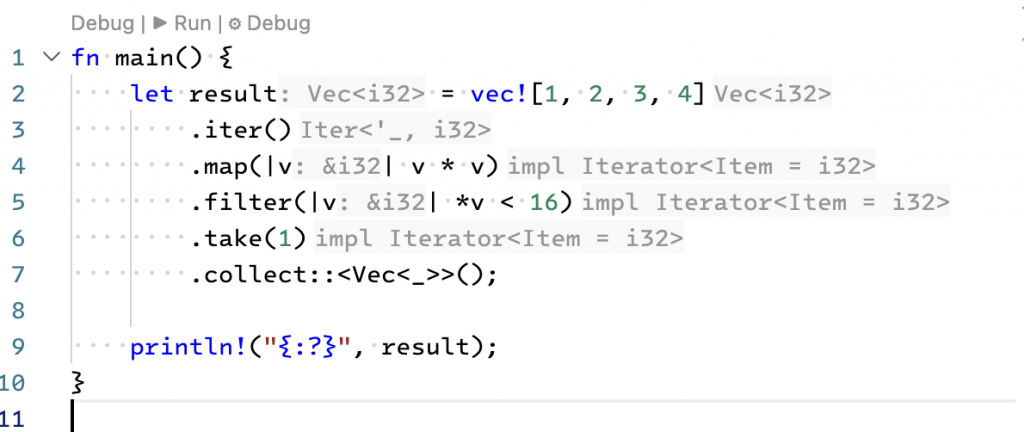

If you use the rust-analyzer plugin in VS Code, you can discover the secret:

It turns out most methods in Iterator return another data structure that also implements Iterator. So they can be chained one after another like this. In the Rust standard library, these data structures are called Iterator Adapters. For example, the map method returns a Map structure, and Map implements Iterator (source code).

The entire process goes like this :

- When

collect()executes, it actually tries to use FromIterator to build a collection type from the iterator, which repeatedly callsnext()to get the next data. - At this moment, the current

IteratorisTake, andTakecalls its ownnext(), which in turn calls thenext()ofFilter. Filter::next()actually callsfind()of its internal iterator. At this moment, the internal iterator isMapfind()usestry_fold(), which again callsnext(), this time callingMap’snext().Map::next()callsnext()of its internal iterator and then executes the map function. And the internal iterator is fromVec<i32>.

Therefore, only at the moment of collect() does the whole chain get triggered layer by layer, and evaluation stops whenever sufficient. Since the code uses take(1), the entire chain loops exactly once, which satisfies take(1) and every intermediate step. So it only loops once.

You may wonder: This functional-style code looks elegant, but with all these unnecessary function calls, performance must be terrible, right?

After all, poor performance is a notorious problem of functional programming languages. You don’t need to worry about this at all. Rust uses heavy optimization techniques such as inline. Thus, this very clear and friendly style performs nearly the same as a C-language for loop.

After introducing what it is, as usual we want to use it in real code. But the iterator is a very important feature. Almost every language has complete iterator support. So if you’ve used any before, this should be familiar — most methods make sense immediately by reading them. So we won’t show redundant examples here. When you have specific needs, you can reference the Iterator documentation.

If the functions in the standard library still can’t meet your needs, you can look at itertools, which is named the same as Python’s itertools and provides many additional adapters.

Here is a simple example:

use itertools::Itertools;

fn main() {

let err_str = "bad happened";

let input = vec![Ok(21), Err(err_str), Ok(7)];

let it = input

.into_iter()

.filter_map_ok(|i| if i > 10 { Some(i * 2) } else { None });

// The result should be: vec![Ok(42), Err(err_str)]

println!("{:?}", it.collect::<Vec<_>>());

}

In actual development, we may aggregate a group of Futures into a group of results that include both successful results and error information. If we want to further filter/map only the successful results, the standard library cannot help — you need itertools’ filter_map_ok().

Special Slice: &str

Now that we’ve learned the normal slice &[T], let’s look at a special slice: &str. As mentioned earlier, String is a special Vec<u8>, so slicing a String gives a special structure &str.

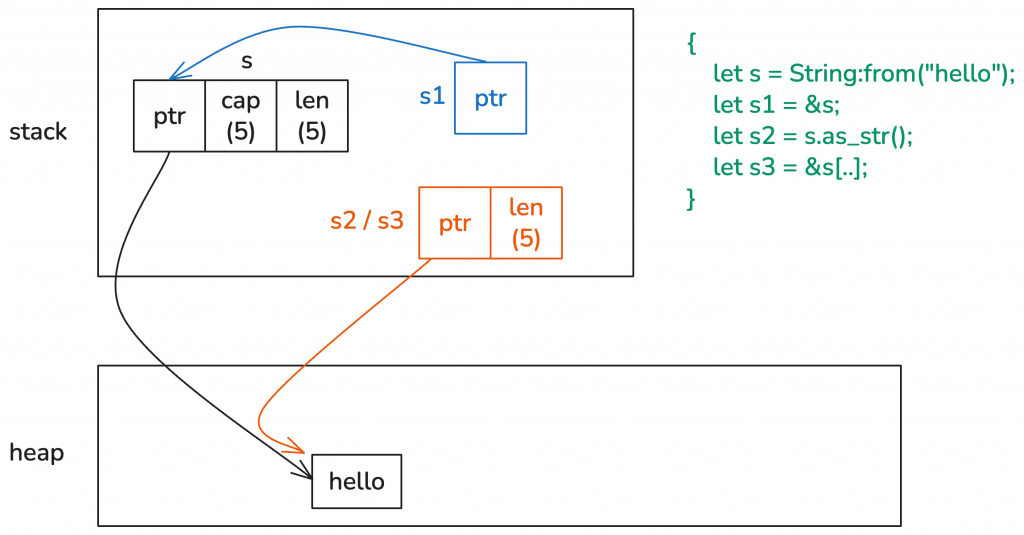

Many people often cannot distinguish among String, &String, and &str. In the previous article on smart pointers we compared String and &str. For &String and &str, if you understood the difference between &Vec<T> and &[T] earlier, then they are the same concept:

String dereferences into &str. We can verify this with the following code:

use std::fmt;

fn main() {

let s = String::from("hello");

// &String will be dereferenced into &str

print_slice(&s);

// &s[..] and s.as_str() are the same and both get &str

print_slice(&s[..]);

// String supports AsRef<str>

print_slice1(&s);

print_slice1(&s[..]);

print_slice1(s.clone());

// String also implements AsRef<[u8]>, so the following code is valid

// The printed result is [104, 101, 108, 108, 111]

print_slice2(&s);

print_slice2(&s[..]);

print_slice2(s);

}

fn print_slice(s: &str) {

println!("{:?}", s);

}

fn print_slice1<T: AsRef<str>>(s: T) {

println!("{:?}", s.as_ref());

}

fn print_slice2<T, U>(s: T)

where

T: AsRef<[U]>,

U: fmt::Debug,

{

println!("{:?}", s.as_ref());

}

Then what is the relationship and difference between a character list and a string? Let’s write a piece of code to look at it:

use std::iter::FromIterator;

fn main() {

let arr = ['h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o'];

let vec = vec!['h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o'];

let s = String::from("hello");

let s1 = &arr[1..3];

let s2 = &vec[1..3];

// &str itself is a special slice

let s3 = &s[1..3];

println!("s1: {:?}, s2: {:?}, s3: {:?}", s1, s2, s3);

// Whether &[char] and &[char] are equal depends on whether the length and content are equal

assert_eq!(s1, s2);

// &[char] and &str cannot be compared directly, so we turn s3 into Vec<char>

assert_eq!(s2, s3.chars().collect::<Vec<_>>());

// &[char] can be converted into String via iterator, and String and &str can be compared directly

assert_eq!(String::from_iter(s2), s3);

}

We can see that a character list can be converted into a String through the iterator, and a String can be converted into a character list through chars(). If not converted, the two cannot be compared.

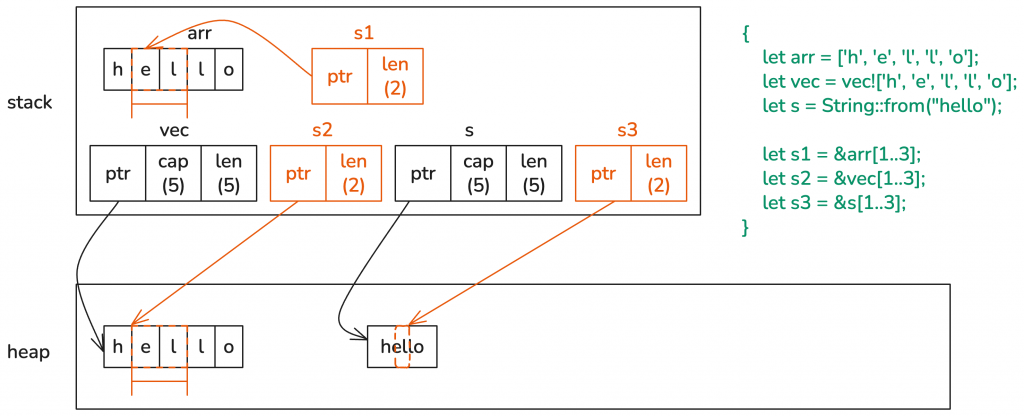

At the end, I placed arrays, lists, strings and their slice together in a comparison diagram to help you better understand their differences:

Are slice references and slice on the heap the same thing?

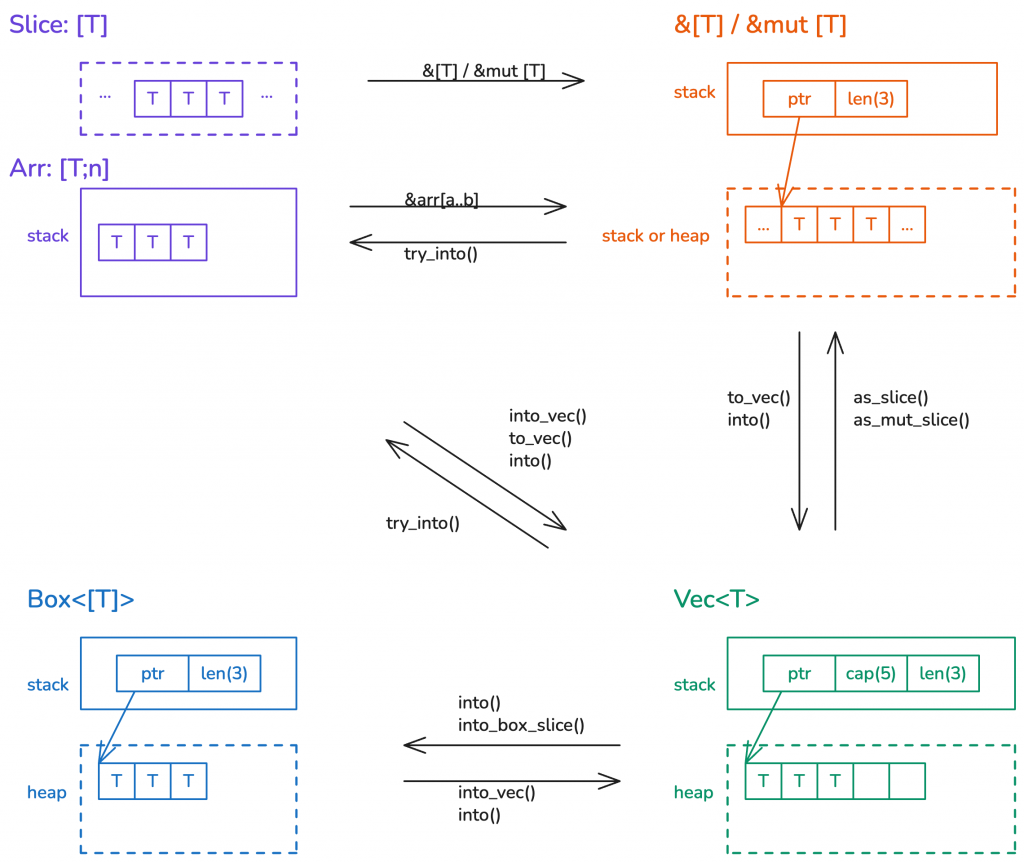

At the beginning we mentioned that slice mainly have three forms of usage: the read-only slice reference &[T], the mutable slice reference &mut [T], and Box<[T]>. We already covered the read-only slice &[T] in detail and compared it with other data structures to help understanding. Mutable slice &mut [T] are similar and do not require further explanation.

Now let’s take a look at Box<[T]>.

Box<[T]> is an interesting type. It differs slightly from Vec<T>: Vec<T> has an additional capacity and can grow; whereas once Box<[T]> is created, it is fixed, has no capacity, and cannot grow.

Box<[T]> is also very similar to the slice reference &[T]: both have a fat pointer on the stack that includes the length and points to the memory that stores the data. The difference is: Box<[T]> always points to the heap, while &[T] may point to either the stack or the heap; furthermore, Box<[T]> owns the data, whereas &[T] is merely a borrow.

![Vec, Box<[T]>, &[T]](https://binarymusings.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/rust-16-06-1024x618.png)

So how do we create Box<[T]>? Currently there is only one available interface: converting from an existing Vec<T>. Let’s look at the code:

use std::ops::Deref;

fn main() {

let mut v1 = vec![1, 2, 3, 4];

v1.push(5);

println!("cap should be 8: {}", v1.capacity());

// Convert from Vec<T> to Box<[T]>, at this time the extra capacity will be discarded

let b1 = v1.into_boxed_slice();

let mut b2 = b1.clone();

let v2 = b1.into_vec();

println!("cap should be exactly 5: {}", v2.capacity());

assert!(b2.deref() == v2);

// Box<[T]> can modify its internal data, but cannot push

b2[0] = 2;

// b2.push(6);

println!("b2: {:?}", b2);

// Note that Box<[T]> and Box<[T; n]> are not the same

let b3 = Box::new([2, 2, 3, 4, 5]);

println!("b3: {:?}", b3);

// b2 and b3 are equal, but b3.deref() and v2 cannot be compared

assert!(b2 == b3);

// assert!(b3.deref() == v2);

}

If you run the code, you will see that Vec<T> can be converted to Box<[T]> via into_boxed_slice(), and Box<[T]> can be converted back to Vec<T> via into_vec().

Both conversions are lightweight—only structural transformations without copying the data. The difference is that when Vec<T> is converted into Box<[T]>, any unused capacity is discarded, so overall memory usage may decrease. Additionally, Box<[T]> has a useful property: unlike Box<[T; n]>, whose size must be known at compile time, Box<[T]> can be created at runtime and will not change size afterward.

Therefore, when we need to create a fixed-size collection on the heap and do not want it to grow automatically, we can first create a Vec<T> and then convert it into Box<[T]>. Tokio makes use of this characteristic of Box<[T]> in its broadcast channel implementation.

Summary

We have discussed slice and the major data types related to slice. slice are an important data type, and you should focus on understanding their purpose and usage.

Today you saw that many data structures are built around slice, and slice abstract them into a common access pattern, enabling a unified abstraction across different data structures—this is a design idea worth learning. In addition, when constructing your own data structures, if their internals contain contiguous equally sized data elements, you may consider implementing AsRef or Deref to slice.

The diagram illustrates the relationships among slice, arrays [T; n], vectors Vec<T>, slice references &[T] / &mut [T], and heap-allocated slice Box<[T]>. It is recommended to spend time understanding that diagram; you can also use the same method to summarize other related data structures you have learned.

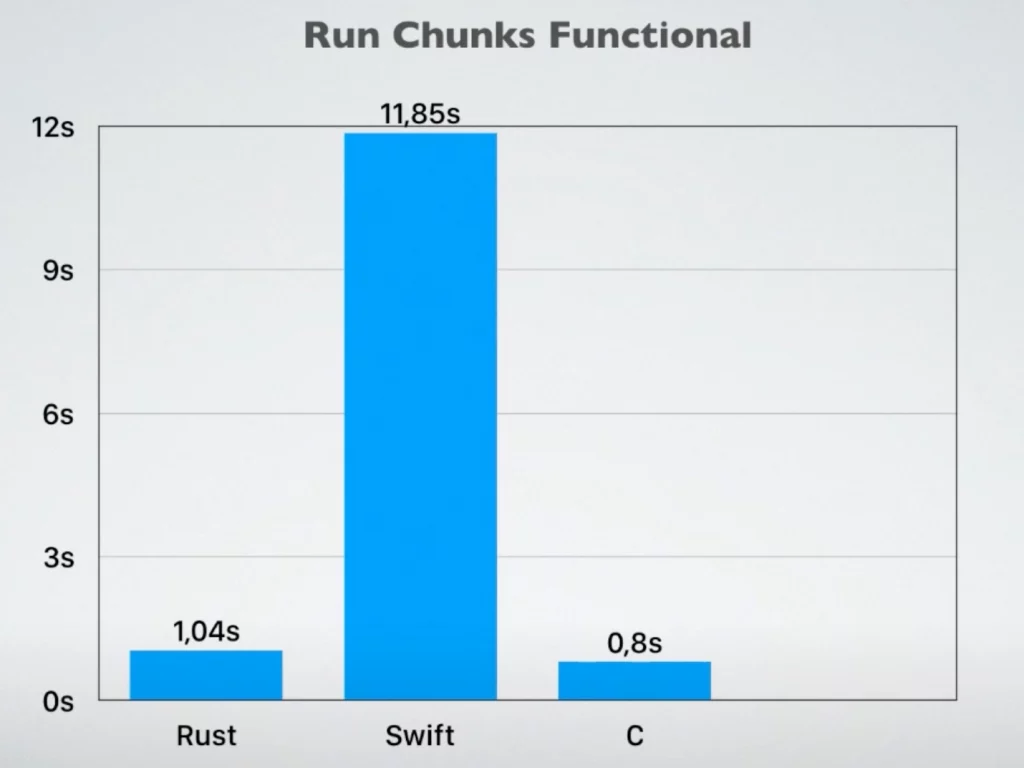

Reference: How fast are Rust Iterators really?

When using the functional programming style provided by Iterator, we often worry about performance. Although Rust heavily uses inlining for optimization, you may still have doubts.

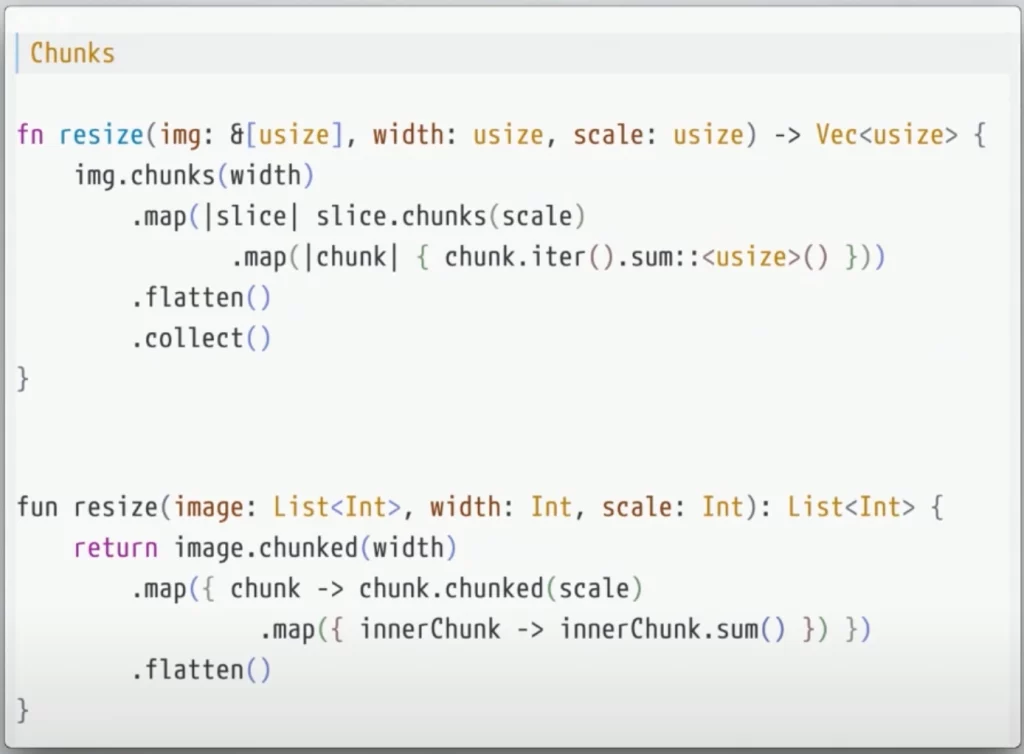

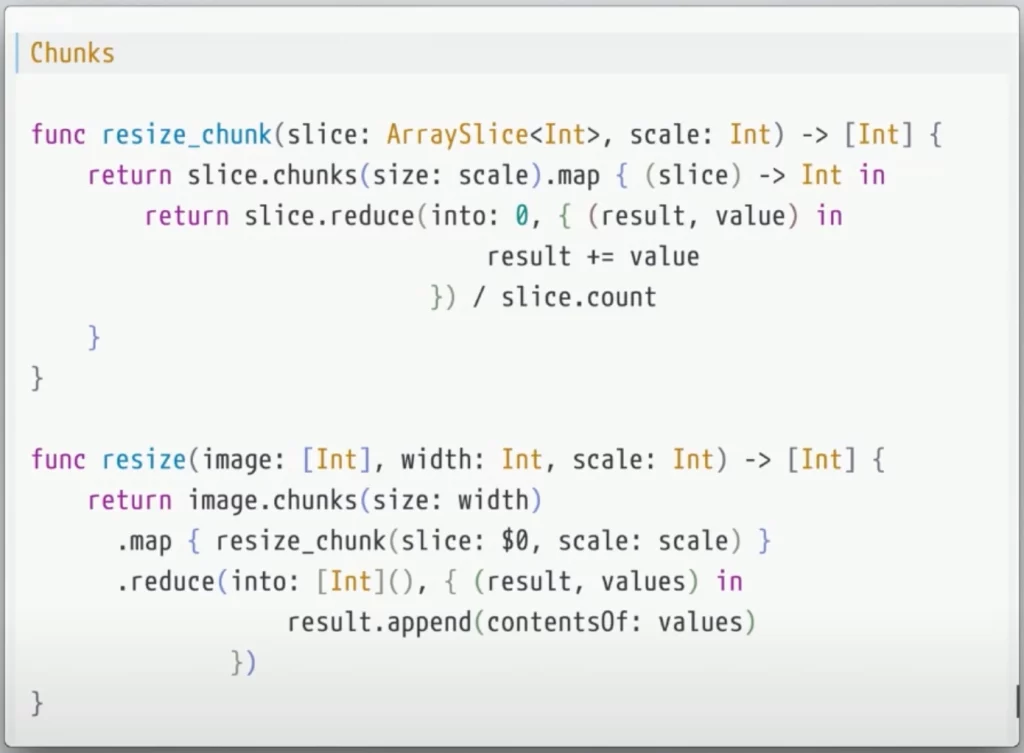

The following code and screenshot are from a YouTube talk: Sharing code between iOS & Android with Rust. The speaker compares the performance of Rust / Swift / Kotlin native / C by processing a large image using Iterators. You will notice that when working with iterators, Rust code looks very similar to Kotlin or Swift code.

The result is that under functional-style processing (C does not have functional-style iterator support, so it used a plain for loop). Rust and C both finish at around 1 second (C is about 20% faster), Swift takes 11.8 seconds, and Kotlin native times out entirely.